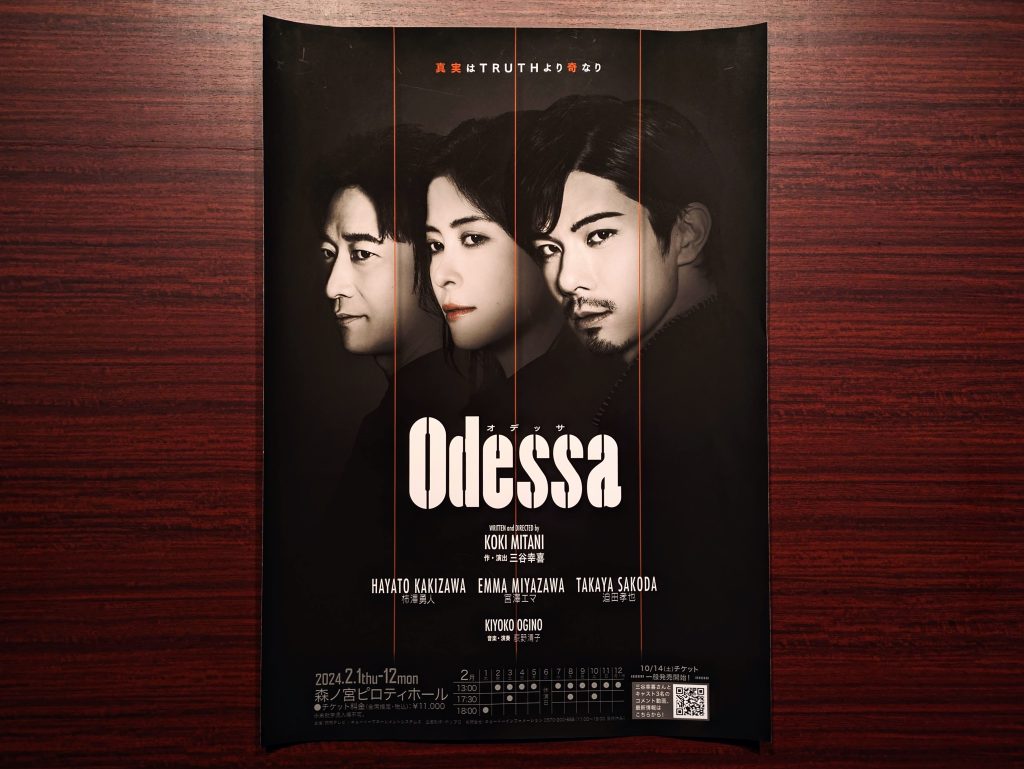

“Three characters. Two languages. One truth.” This is the idea behind Odessa (オデッサ), Koki Mitani’s first new play in three and a half years, set in 1999 in the American town of Odessa, Texas. A Japanese tourist is detained on suspicion of murder. The detective, while of Japanese descent, only speaks English. And so an interpreter, a Japanese student studying abroad, is brought in to translate. But as the tagline tells us, “現実 (genjitsu, ‘truth’) is stranger than TRUTH.” Confused? Hell yeah.

Kōki Mitani is pretty much the theater world’s version of Juzo Itami: a sensationally multitalented artist who writes and directs all of his own productions, frequently re-casts the same groups of actors in everything he makes, working to create intertextual comedies that are often inspired by American sensibilities… He’s even, fittingly, the recipient of last year’s Juzo Itami Award, which honored his achievement and outstanding talent in many of the same areas Itami worked. And while, also like Itami, he’s (for some cruel and baffling reason) practically unheard of in the West, writer Nobuko Tanaka starts off her 2012 article and interview in the Japan Times about his domestic popularity with a simple fact: “Koki Mitani is far and away the nation’s best-known dramatist.”

62-year-old Mitani has written and directed over 50 stage plays, a truly staggering achievement, and he shows no signs of slowing down. His ceaseless creative output is likely a factor of how he views work – as the interview I linked above elucidates, writing is not “working” to Mitani, but simply a natural extension of his passion, hobby, and interests, and thus definitionally “work” is what he is doing all the time (…whether that’s a healthy mindset or not). In addition to writing for the stage, he also writes and directs on the screen, having created nearly three dozen TV dramas and eight films (his ninth is due out later this year). The most famous of these is Furuhata Ninzaburō, often described as “the Japanese Columbo”, which ran between 1994 and 2004. It’s beloved enough that one of my former coworkers (in his mid-20s!) gave his farewell speech to a couple hundred other employees in-character as Furuhata, dressed in his signature black coat and replicating his idiosyncratic vocal tics and body language. I later learned that he regularly does these Furuhata impressions at nomikai, to everyone’s amusement. I’m still kind of in shock.

Mitani’s feature films (many of which started out as plays) are a delight too. This is in large part because they feel like performances, carefully pieced together dramatic enactments, using very few cuts, along with framing that often lets us see an entire “stage” worth of goings-on. Mitani notably does not use a computer either, in work or his personal life – he works in the analog. While I could go on and on about the wondrous Welcome Back, Mr. McDonald (1997), The Magic Hour (2008), or The Uchōten Hotel (2006), I’ll let my friend Jai’s video essay on him do the talking instead, and you’ll hopefully leave convinced that you should go get to know some of Mitani’s films.

Honestly, I did not understand everything that went on in this play. It was great, and hilarious, but I think it would even be difficult for native Japanese speakers to fully wrap their heads around, especially given that the promotional website directly asks audiences, “Can you keep up with the speed?” Odessa is a conversational drama with one act, one set, and which takes place in a single room, entirely driven by fast-paced dialogue between three characters. And it is this dialogue that is the play’s vehicle of choice for deceit – either of other characters, us as the audience, or both. Its story focuses on misunderstanding as a phenomenon in itself, and features multiple languages (Standard Japanese, the Kagoshima dialect of Japanese, and English), with interactions between characters built around different domains of information and disinformation. Here’s what happens.

The story

A narrator (Eiji Yokota) starts out by telling us that the town of Odessa, Texas was named by immigrants due to its similarities with Odesa, Ukraine, a sparsely-populated city which had its population flourish due to the construction of oil wells. After the natural resources were depleted and the drilling sites abandoned, it again became desolate. This town in Texas is where our story takes place. (NB: I don’t think this is exactly true, but…)

A student named Steve Hidaka (Hayato Kakizawa) who’s studying abroad in the US and a Japanese American detective, Inspector Kaczynski (Emma Miyazawa), are alone in a diner. Kaczynski explains that she’s investigating the death of an old man in the town but, due to the fact the rest of the police force is heads-down focusing on the 17 serial murders that have occurred elsewhere in the state, she’s the only one assigned to this particular case, and the diner will be serving as the interrogation room. This case is outside of her department, too – her usual focus is reports of lost property. Kaczynski explains that a Japanese tourist has been detained as the suspected murderer but she cannot communicate with him, as he only speaks Japanese, and she only speaks English. And thus, we understand, she has hired Steve, who is bilingual, to serve as an interpreter between the suspect and herself.

The intended audience realization at this point is that, while all dialogue so far has been spoken in Japanese, we should now (implicitly) understand that, diegetically, the characters have been talking in English, and the current conversation is simply being “translated” back into Japanese for the sake of the audience.

Kaczynski realizes she has forgotten to buy apples for her son’s lunchbox at 7-Eleven, the nearby convenience store, and says she’ll be back soon. Shortly after she steps out, an armadillo rolls into the diner. Steve feeds it. Boy, this sure is a small town in the Wild West.

A Japanese tourist enters and introduces himself as Kojima Kantaro (Takaya Sokoda). Steve realizes he’s the accused murderer, and keeps his distance (only after grabbing what looked like a magnifying glass to defend himself), but is also happy to meet another Japanese person in the town. In conversing, the two quickly discover that they’re both from Kagoshima Prefecture – part of Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands. Steve is from the city of Makurazaki and Kojima’s from Ibusuki, so the two naturally connect over being able to converse in their native dialect. (Language, such an important part of identity!) Steve asks Kojima where he’s been staying, and he admits that he’s been sleeping outdoors for the past three days. He says that he came to the US aimless and with no money after becoming disillusioned with his job as a police officer in Japan, and the reason he came to the very non-touristy town of Odessa in particular is because it sounds similar to the word “otessaa“, a term of address in Kagoshima dialect.

As Inspector Kaczynski returns, the wall behind the characters moves backwards and she begins speaking in English, with Japanese subtitles suddenly appearing on the blank upper portion of the wall, which turns out to actually be a screen. (This shifting wall, we come to learn, is the sign for if the conversation is being magically “translated” into Japanese for the audience or not, and indicates how we should be imagining the scene. When it’s far away, i.e. when only Steve and Kaczynski are present, this designates that they are, in the world of the play, actually speaking in English.)

Kaczynski finds the armadillo, and says it is her pet, Irma. She then explains the situation to Steve: a long-time resident of the town, an elderly man in his 80s, was recently brutally murdered on the side of the road, and the only witness, the man’s 35-year-old son, stated that he saw a Japanese man who looked like Kojima in the vicinity. The man had also taken out the equivalent of $3000 from his bank account that morning, and it was missing, which she suspects was the motive for his murder. The Japanese translation of Kaczynski’s lines moves across the screen in Star Wars opening crawl-style perspective projection as she speaks (to allow the audience to read along, and understand what’s being said). When Steve interprets this into Japanese so Kojima can understand, though, Kojima suddenly declares, “That was me, I did it! I’m the criminal! Please prosecute me!”

But Steve has built some rapport with Kojima, feels a kinship with him as they’re from the same place, and empathizes with his mental state. He realizes why he is confessing… because he’s in a small town, in distress and depressed, without money or a place to stay, without being able to speak the language, and has surely decided his life might as well be over now that he’s been falsely accused and arrested. How could he not want to help someone in that situation? So when Kaczynski asks Steve what Kojima said, he replies, “He says that he did NOT do it! He’s innocent!” (Of course, not understanding English, Kojima doesn’t know that his admission of guilt has not been accurately conveyed.)

Steve tells Kaczynski that he also believes Kojima to be innocent, but she rebukes him, saying it’s not his job to ask questions or give his opinion, but simply to be an interpreter. While Steve is providing on-the-spot false translations to both, back and forth, the two grow wary. Kojima doesn’t understand why he’s not immediately being locked up, as he’s admitting to the crime, while Kaczynski is sure that the two are having side conversations. “He’s been speaking for so long, and you haven’t translated anything! You’re just talking to him directly!” She reminds him that, again, he should not be speaking with Kojima on his own, just providing direct translations for her.

To prove his guilt, Kojima begins miming out the murder, explaining how he knocked the man to the ground and began bashing in his head with a rock. “What is he doing?!” Kaczynski asks. “Oh, you see, he’s the owner of a soba shop, and he’s explaining how to make soba noodles! That’s how you knead the dough, hammering it down hard with both hands!” “Soba??? Why is he talking about soba all of a sudden?” Switch to Japanese, Kojima: “Wait, did she just say soba? Why is she talking about soba?” “No, no, she didn’t say SOBA, she said SOVA! It’s an expression in English… It stands for Situation Of Violence Action! She’s asking about your motive for the murder!”

This gestural re-interpretation and deception goes on. For example: Kojima collapses on the ground crying, feeling guilty. “Why does he have his face on the floor like that?!” “He really has to go to the bathroom!” Kojima gets up and begins pacing around. “Wait, what about the bathroom? Didn’t he have to go?” “He has… suppressed… the urge!”

He falls to the ground again, apologizing, repenting. “What’s he doing on the ground now?!” “He’s able to smell the… armadillo pee!!! From before! He’s reacting to how disgusting it is!”

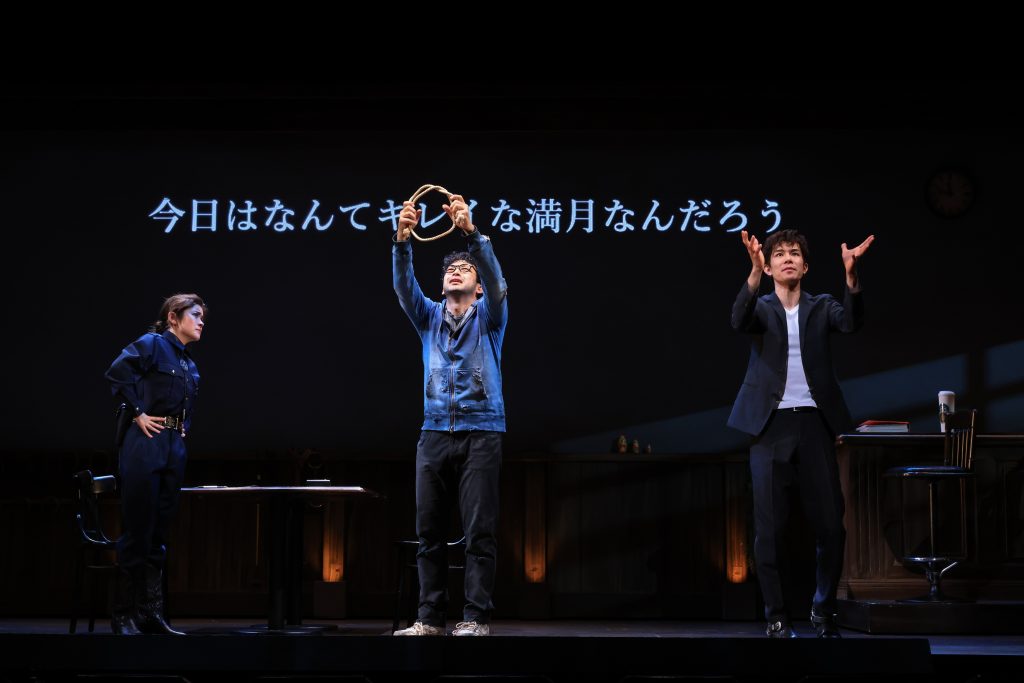

He finds a rope and is able to fasten it into a noose, and places it around his neck. “Why is he trying to hang himself?” “He’s not, he’s telling you it’s cold outside, and that you should be wearing a scarf!!! You need to wear this to stay warm!”

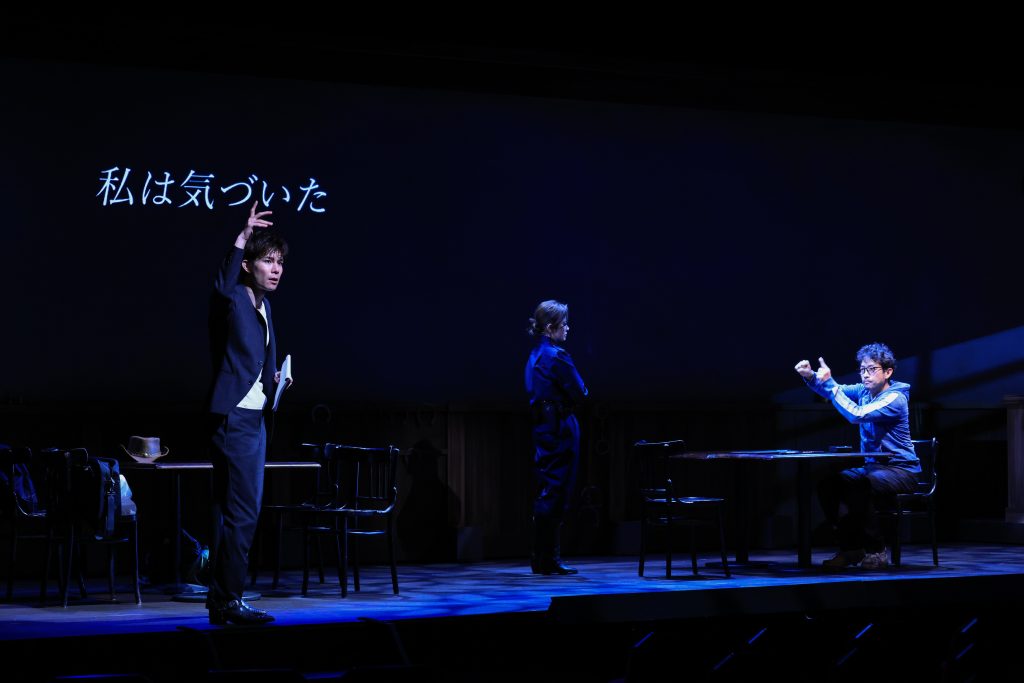

As Steve continues to talk with Kojima in Japanese on the side, Kaczynski again accuses him of having unrelated conversations, but he “explains” that Kojima was simply reciting a poem. Steve says that the difference in sentence lengths are due to Japanese being a very efficient language, allowing people to convey beautiful expressions in only 17 characters, as in the traditional 5/7/5 structure of haiku. He also says that this is why Kojima was on the side of the road in the first place, in search of inspiration to write poetry. “Well, where’s the poem then?” “…He writes his poetry in his head! He was living in the moment, enjoying the beautiful landscape and creating the poem in his mind!” “What landscape? It’s just an old, barren, dirt road in a decaying town with absolutely nothing around! If he really has a poem, let’s hear it.”

And so Steve recites a poem (of his own creation, naturally) about the vast open sky of Odessa, the rich brown and red of the dirt roads… and Kaczynski begins crying. She says she feels ashamed for having never realized how beautiful the world around her was, simply taking it for granted, unable or unwilling to view it as anything more than mundane. “That was beautiful,” she says. “Thank you,” Steve replies. “…………But you were just translating.” “………..I still take pride in my work.”

Kojima has to go to bathroom for real this time. Steve explains: “The urge… has returned!” He’s allowed to go, and walks up the stairs off the stage. (Now that only two interlocutors are present, both of whom speak English, the wall moves forward, the subtitles disappear, and the play’s language returns to Japanese to make it easier for the audience to understand – even though in the world of the play they’re still supposed to be speaking English. This was confusing to me at first, and of course it made things harder for me as a native speaker of English and not Japanese; I don’t think it was strictly necessary, but I understand why Mitani did it, and it provided another interesting layer to figure out.)

While Steve and Kaczynski talk alone, she admits that she has come around to believing that he is not the culprit – a pure-hearted person with the ability to write such a beautiful poem could never be capable of committing murder, especially of a senior citizen. The two begin discussing their bilingualism and identity. Steve says that his English is passable, but he does not feel like he has true mastery over it. For example, he saw a sign at a pool the other day that read “No Dogs or China”, and was worried that he would be kicked out because of racism and because many Americans cannot tell Asians apart. But Kaczynski asks, “was there a pottery show nearby?” and Steve says there was. She explains that “china” has another meaning, referring to fine ceramics, and the pool’s sign was simply saying that it was dangerous to bring china into the pool! D’oh! (This is a reference to a folktale of a supposed sign in Huangpu Park within the Shanghai International Settlement from the late 1800s and early 1900s.)

Kaczynski talks about her own experience with language, race, and identity, and shares her reason for becoming a policewoman. She says that her mother, a lawyer, is Japanese, but she didn’t want to grow up to be like her, so instead she followed in her Polish father’s footsteps, who is a police captain in New York. This is also why she rejects her Japanese heritage, continuing to live and work in the US and not learning any Japanese.

When Kojima returns from the bathroom, Kaczynski hugs him, apologetic that she was convinced he was a criminal. She asks, in her best attempt at very basic Japanese, for him to please teach her how to make soba, and to share his skills and knowledge with her. He is, naturally, confused. He says, “But I committed the murder!” Steve continues to convince Kaczynski that he did not, such as by pointing out that the old man had his money stolen, but Kojima has none on him, demonstrated by the fact he had been homeless for the past few days. He also re-enacts making soba with her, showing her how to stretch the noodles, and the two share a tender moment.

The two also discover that the old man had a leather holster on him, but it was empty, meaning the killer had taken his gun. But the old man was bludgeoned, not shot… does this mean that the killer doesn’t know how to use a gun? Kojima had been a police officer, so he should know his way around a gun… but the man’s son would not – after all, he’s an activist who regularly protests against the National Rifle Association! Steve explains this all to Kojima, but he still refuses to admit that he’s not the murderer and continues his attempts to incriminate himself. He says he can procure the stolen gun, receives permission to go retrieve it, and leaves the diner.

While Kojima is gone, Kaczynski and Steve begin to suspect that the first person to discover the body, the man’s son, is the real murderer. Kaczynski then receives a call from her young son, who is home alone due to her long working hours. She plays an English-language version of shiritori with him on the phone. Steve joins in and begins using many bizarre English words such as “biceps brachii” and other muscle-related terms (for some reason…) Kaczynski accidentally says a word that ends in the letter “x” which is the losing condition they’ve invented for the game, per house rules, and their phone conversation wraps up.

Kojima returns with a gun marked with “C.A.”, the victim’s initials – surely he’s the killer! But right then, Kaczynski’s phone rings again, this time with a call from a fellow police officer who tells her that the man’s son has turned himself in, confessing to the crime in full detail, knowing they were getting closer and closer to finding out the truth. Kojima is deemed innocent, despite his claims otherwise, and Kaczynski says they’ll put him up in a motel for the night, as he is otherwise homeless. Steve finally reveals that he has been lying the entire time, mistranslating everything that had been said in order to defend Kojima. Kaczynski slaps Steve, who in turn slaps Kojima.

The two return to their earlier conversation about growing up in Kagoshima, and Kaczynski gets another phone call from her son, distraught that the 7-Eleven apples from earlier had turned brown. She tells him to soak them in a saltwater solution to prevent further browning, and says goodnight. On his way out of the room, Kojima offers a suggestion, saying that it’s better to soak apples in sugar water instead.

Wait. Wait a god damned minute.

Steve didn’t translate Kaczynski’s English phone conversation into Japanese. Yet Kojima still understood, and then made a comment about it. Does this mean Kojima was really able to understand English all along? He was just pretending to only speak Japanese? In that case, and if he really understood everything that was being said, why would he try to take the blame for the murder? ………Unless it was because he was trying to get prosecuted for this murder instead of a much, much more heinous crime. Like the other 17 serial killings. Oh, god.

They pull out the police sketch. It looks exactly like Kojima.

Kojima comes back into the room with a gun. His previous shyness and meek demeanor are gone, and his voice has noticeably dropped at least an octave. His ikemen voice is out in full force. Steve gets scared and grabs the magnifying glass again. For the first time in the play, we hear the actual truth: that Kojima was actually born in London, and is a native English speaker, having moved to Kagoshima when he was ten years old… but he was never quite able to fully pretend he was from there. He was mocked in the police academy for his deficient Kagoshima dialect, forever branded as an outsider, unable to truly fit in. He eventually lost his gun, got fired and, feeling miserable about his life, decided to come to the US to kill people before ending his own life. He snidely tells Steve that Kagoshima dialect is strange, putting down his accent, and runs out of the room. Kaczynski gives chase.

Steve starts feeling depressed, wondering why the killer scolded him for his natural way of speaking. The pride he felt from his first interpreting job begins to dissolve. Suddenly, he hears a gunshot outside. Someone must’ve been shot! Inspector Kaczynski returns, alive, and explains that she did not shoot him – he slipped on armadillo pee and fell into a well. Chekhov’s armadillo! She also admits that she was transferred to the small town of Odessa from New York due to a drunken stupor in which she lost her gun and police car, somewhat similar to Kojima’s story (?!) She goes to wrap up the case and leaves.

Steve is alone, and begins playing shiritori with himself via keywords of the play: poem… motel… logic… china… armadillo… outsider… relax.

The end. (Punctuated by a big, lit-up “Otessa” appearing in Broadway-style lights. A gunshot to the cross stroke of the ‘t’ causes it to fall to the ground and become “Odessa”. People clapped enough that the actors came back on stage to bow three times! Lots of teasing, playful waving from off-stage too.)

Discussion

God, this was such a fun play. I poked through a few blogposts by Japanese theatergoers and saw rumors of of cameras at one of the Tokyo performances, so maybe a filmed version will be released someday?! This seems like one of Mitani’s plays that would work just as well as a film, even just a video of the stage in one long single take, like his incredible Airport 2013 (2013). It bears a striking similarity to the two-person University of Laughs, a much older play of Mitani’s about freedom of expression, working around censorship, and creativity via constraint. (This one was even adapted into English and performed on London’s West End with the title The Last Laugh.)

There’s also some overlap with The Magic Hour (trailer here) – “Cut! …No, I wasn’t saying ‘cut’ like this is a movie, that’s Della Togashi’s nickname! His close friends all call him ‘Cut’!” – which I’d think would stand out to anyone who’s familiar with the film. While Odessa was definitely a typical Mitani piece, it didn’t seem repetitive or recycled in any way, and its aforementioned similarities his previous works came to me only in retrospect while writing this.

Odessa made great use of its actors’ natural talents, and it makes me wonder if it was specifically written for them; Emma Miyazawa served as the play’s English supervisor (as a native English speaker) and Hayato Kakizawa as the Kagoshima dialect coach (as he’s from the region, a native speaker of that dialect). All three actors also appeared in Mitani’s previous TV work. As a sociolinguist, I loved how the play at times touched on more subtle forms of prejudice, such as linguistic discrimination, judgment based on speech, and perceptions of what contributes to prestige and marginalization. There was also some discussion of discrimination due to linguistic barriers, and the act of changing one’s name to fit in with a new culture or place (which I believe Steve did when he decided to study in the US), but I don’t really remember all these parts well enough to accurately write about them here – just another reason I’d love to go see it again. (There was also a very brief part about blueberry yogurt which then turned out to be expired that I didn’t really understand? I think this was just because Yakult was a major sponsor of the production… ahh, product placement.)

The play is certainly a farce, most of its situations and conversations wildly improbable and silly, but what was more entertaining and thrilling than figuring out the identity of the murderer was anticipating how Steve would cover up, explain, and “translate” away Kojima’s increasingly ridiculous gestures, which then uncovered more sides to the case. I loved the inventiveness of the subtitles, which almost felt like a fourth character in themselves. They were dynamic, much like how comic book or manga sound effect lettering might be if animated – huge, exploding letters for when Kaczynski at one point shouts “STOP!”, carefully-arranged characters in a classical typeface for the poetry, falling off the screen one-by-one if a character trailed off in the middle of a sentence. The shiritori sequences were also in color and animated, the final letter of one word shifting left and becoming the initial letter of the following word. And sometimes a picture is worth a thousand words: the clipart-like visual aid depicting “man slipping on armadillo pee and falling into a well” was both unexpected and hilarious. The Horipro Stage YouTube channel recently uploaded a short clip of the play and subtitles if you want to get a sense of this for yourself.

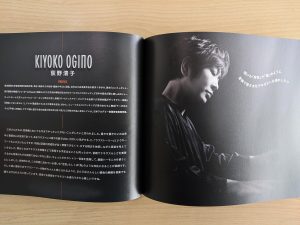

One final aspect of the performance that I didn’t capture above is that there was some light piano music performed by Kiyoko Ogino at pivotal scenes; her piano was on the left of the stage and dimly lit the entire play. (Mitani is certainly no stranger to involving music in his works.) On the way out of the theater, I saw that… they were selling seats to other, future musicals in the lobby? Apparently this is something they do in Japan, and it’s kind of smart?? Because of this, I found out that the same production company is bringing my favorite musical to Japan this year: Come From Away… meaning I’ll get to see it in-person again, this time fully adapted into Japanese. So excited. I got tickets for when it comes to Nagoya in April!

To end, here are some selected photos of the play’s program – a pretty high-quality book I was able to buy before the show started (for ¥1800, not horrible but more than I expected) which includes an introduction from Mitani, some thoughts that each of the actors and the musician shared about the show, an interview with Mitani by a University of Tokyo Shakespeare expert, a talkback with the actors, and a piece on the process of creating the dynamic subtitles. (As a not-fan of celebrities and celebrity culture, I didn’t include the actors’ bios, model shots, or the photoset from a rehearsal.) I sadly don’t have the time or energy to translate the pages here, but if you’re interested, hopefully Google Lens or DeepL or your choice of other machine translation software can help!

this was so entertaining to read, and not just cause my video’s in it!! I loved this so much

Thank you Jai!!! I’m so glad :’D

absolutely wonderful piece, thank you! really enjoyed reading

Super happy to hear it, thank you for taking the time to leave a comment!

Great write up! Sounds like it was a lot of fun in person!

It was! Such a blast. Here’s hoping it gets released on DVD/BD or something someday :’)

Hey Eli,

looking for something to do in Japan during the next two weeks, I stumbled upon your review. I had to stop myself halfway through your synopsis from finishing this fascinating read in the entirely unlikely event that Odessa gets adapted/translated or I learn Japanese and come back for a rerun. I love dramas that write dialogues of characters with different bodies of knowledge well, ever since reading Sartre’s No Exit. That being said, while such a use of language for a transnational narrative might not be entirely unheard of, I feel like a Japanese-American story involving Law Enforcement would add so many layers. Thank you for this write-up, even if it ended up being a huge tease for me ;’)

Thanks for your kind comment, Artur!! Like you, I am really hoping it might someday get adapted for the screen or even just released as a filmed version of the stage show, or something. Hell, even the script for it, in all honesty… I’m vaguely familiar with No Exit but have not ever read it. I really should! I loved seeing Annie Baker’s The Antipodes a few years back which, from the amount I know, seems in the same vein as some of Sartre’s work. Definitely philosophical and existentialist, stories about stories, and about theory and categorization…

Are you familiar with the game Kentucky Route Zero? So many literary references and allusions, including to Sartre (and Beckett, and O’Neill, and so on), and I get the feeling from your thoughtful comment here that it would be right up your alley… to note, it feels a lot more like reading a book or watching a play – blending a magical realist Americana story of reality and fiction – than the standard conceptualization of “playing a game”. Highly suggest you take a peek. :) If you do, enjoy, and thank you again! And have a great time in Japan!

This was a great read, thank you so much for posting. I came to this website cause of a train map I saw reddit, did not expect to get really great theatre reviews from it :)

Ahhh, thank you so much for the kind words and taking the time to comment! Hahaha, yeah, this has definitely started to veer toward becoming a place for me to write about travel & trains but I also, admitted, enjoy some great live theater!! I haven’t been to any in quite a while so I should probably fix that :) So glad you enjoyed and I hope you’re able to check out some of Mitani’s movies (or plays)! They’re all so great!