Ever since I began planning my move to Japan in mid-2023, there was one place I promised myself I’d go at the first possible opportunity: the Itami Juzo Museum (伊丹十三記念館 / Itami Juzo Kinenkan) in Matsuyama, Ehime Prefecture, on the island of Shikoku. Shikoku is the smallest and least-populated of Japan’s four main islands, and I’d never been off Honshu, which added to my excitement. So with a full week off work for the New Year’s holidays, I made the trip.

Juzo Itami is my favorite film director in the world, a true visionary and master of subtle social satire and life-affirming comedy who dared to poke fun at and push back against his own rule-bound culture’s customs (“I make movies to get the Japanese to look in the mirror”, he said in 1996). He made his directorial debut at age 51 after spending decades as an actor and essayist… and editing a 1980s psychoanalytic magazine, designing commercials, illustrating print ads, translating Western cookbooks, living in London and becoming fluent in English and French… After writing and releasing ten feature films, he was murdered by the yakuza in 1997 for criticizing them and mocking their practices, remaining unafraid after a prior violent attack and continuing to investigate their ties to a religious cult. I can only dream of what the film and literary landscape could have looked like today if he had been able to keep making movies into the 21st century.

As an aside: Here’s my ranking of his movies on my Letterboxd, showcasing my favorites, plus thoughts I’ve written about some of them. Despite being a household name in Japan, he’s relatively overlooked in the West, with Tampopo (タンポポ) being his most well-known work outside of Japan. Billed as a “Ramen Western”, Tampopo is a paean to life, an ode to food and pleasure and its importance in all aspects of the human experience that serves as his magnum opus – but, looking at Itami’s filmography as a whole, his other movies are criminally underwatched. While Tampopo (deservedly) has over 100,000 views on Letterboxd and 22,000 ratings on IMDb, only two others even crack 5000 watches, with some even below 1000. This is, frankly, devastating, and I will be shouting from the rooftops until it’s remedied.

For example, A Taxing Woman (マルサの女 / Marusa no onna) is definitively the most entertaining film you will ever see about a forensic tax investigator, with an insanely funky jazz soundtrack to top it off, and Supermarket Woman (スーパーの女 / Super no onna) and Minbo: The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion (ミンボーの女 / Minbo no onna) are likewise filled with so much inimitable fervor and richness. Almost all of his films star his wife, Nobuko Miyamoto, in the lead role, and all can be rented for streaming on the Criterion Channel or found on the Internet Archive. In other words: Please, please, please watch some Itami movies.

Deal? OK! Back to the blogpost.

Alternatively called the Juzo Itami Memorial Museum (a more accurate translation for the word kinenkan, and darn that Japanese name order!) the space serves as a celebration of Itami’s life and work. Nobuko Miyamoto, as his widow, was instrumental in putting it together, and serves as its director; it opened on his birthday in 2007. It’s a bit outside of the downtown core of Matsuyama, but is very easily reachable via train or bus. After paying ¥800 (only USD $5.40 at the time of this writing) for one adult ticket, the main exhibition area is located through a sliding frosted glass door… with Itami’s face peeking through, playfully welcoming you in.

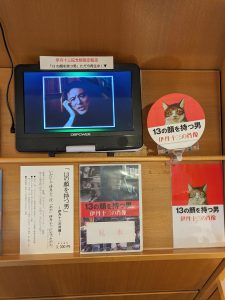

The 13 faces of Juzo Itami

“Juzo Itami” – or, more accurately, “Jūzō”, if James Hepburn and his romanization system have anything to say about it – is a chosen name. He was born Yoshihiro Ikeuchi, much to the chagrin of his father Mansaku Itami, also a film director and satirist, who wanted to name him Takehiko. Unable to deal with a son breaking the familial tradition of including the character 義 yoshi (“righteousness”) in boys’ names, his grandfather overruled his father. But while he was Yoshihiro on the dotted line, to his family and in all close relationships throughout his life, he was Takehiko, or Taka-chan as a nickname, even past childhood.

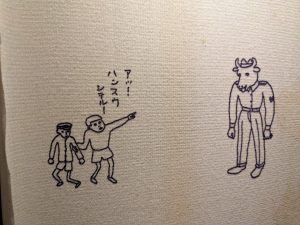

The stage name 伊丹一三 Itami Ichizō was given to him when he joined the studio Daiei Film in his late 20s, a combination of his father’s last name and the given name of Kobayashi Ichizō, the founder of Hankyu Railway, Toho, and the Takarazuka Revue (…stay tuned for the post coming later this month!!!)

He was credited as 一三 Ichizō in multiple of his early roles, but in his 30s he added an extra extra vertical stroke to it – in his words, “to turn a minus into a plus”1マイナスをプラスに転じる

All translations by eli fessler. – thus becoming 十三 Jūzō. The kanji 一 and 三 mean “1” and “3” respectively, but by changing the first one to a “10”, his new name took on the meaning of “13”. For this reason, and the fact he worked in such a multitude of areas, much biographical work about Itami has been themed around the concept that there were thirteen sides to him, each as rich and complex as the other. The museum’s first room, housing its permanent exhibition, aimed to present his 13 different “faces” to visitors.

1: Takehiko Ikeuchi

In an alcove to the left of the first section are a couple rows of benches and a TV, projecting a 2-minute welcome & thank you message from Nobuko Miyamoto. This area is also used to screen one of his films at 13:00 (1 p.m.) on the 13th of most months of the year. Alternating with Nobuko’s welcome is a selection of 特報 tokuhou “news flash” items featuring Itami himself dressed as characters from his films. These are different from traditional movie trailers in that they’re produced before movies are finished shooting, and thus are comprised of all-original content to promote the upcoming film. Luckily, someone has uploaded most of them to YouTube, so they can be watched online! The museum was showing these five:

- Marusa no Onna 2 (A Taxing Woman’s Return) – not online

- A-Ge-Man (Tales of a Golden Geisha) – not online

- Minbo no Onna (Minbo: The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion)

- Daibyonin (The Last Dance)

- Super no Onna (Supermarket Woman)

In the clip from the Marusa no Onna 2 news flash trailer below, he’s dressed as the man in the white suit from Tampopo?!

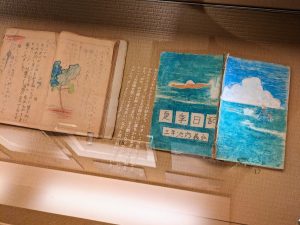

The main part of this first section showed drawings he did and photos of him from his childhood, with his family and at school, and talked about the origin of his stage name, which I wrote about above.

Gallery text. I’ll be showing these for all 13 sections, so use Google Lens to poorly-but-still-usually-passably-machine-translate them if you want!

2: Music aficionado

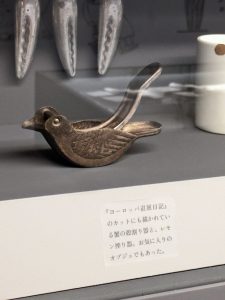

The second of Itami’s faces is that of a man who loved music, and who viewed it as an essential part of his life. Itami’s father was diagnosed with tuberculosis and died while he was in middle school, weighing on him heavily. He left behind a gramophone, which Itami took with him when moving to Matsuyama for high school – his parents’ hometown – and while he was living in a boarding house with a piano, began listening to classical composers such as Bach and Mozart. Following his move to Tokyo after graduating, he took up violin lessons at the age of 21, and also learned to play guitar. In one 1965 essay collection titled Diary of Boredom in Europe (ヨーロッパ退屈日記 / Europa taikutsu nikki) – a digest of thoughts from traveling on-location while acting in foreign films – he wrote, “I think that a musical instrument is a person’s lifelong friend. It’s a friend that will never betray you. I feel this from the bottom of my heart.”2思うに楽器とはその人の終生の友である。決して裏切ることのない友である。わたくしは心の底からそのように感じるのであります。

All translations by eli fessler. He was adamant, though, that one does not have to start learning an instrument at the age of three or four; perhaps you may not be able to become a professional, career musician, but he believed it was never too late to learn for the purpose of enjoying yourself.

The books of Carl Flesch were Itami’s greatest teacher.

3: Commercial designer

In 1954, still in the same year he had graduated from high school, Itami changed from working as a film editor to a commercial designer. He designed book covers and hanging in-train advertisements (a common occurrence in Japan), a skill which led him to later design the posters for his own films. He became especially well-known for his detailed lettering, and film director Kajirō Yamamoto (mentor to Akira Kurosawa) said his serifed Mincho writing was the best in Japan, if not the world.

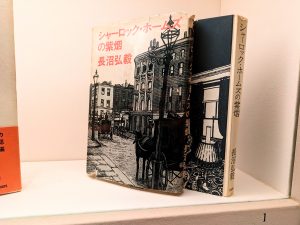

4: Actor

Itami was an actor for decades before he became a film director, and acted in over three dozen movies and two dozen TV dramas during his life. He got attention for his work in the 1965 British film Lord Jim, an adaption of the Joseph Conrad novel – after all, he was a Japanese actor who spoke fluent English, and in the postwar era, too – along with the starring role in a Tale of Genji adaptation that same year and a number of NHK Taiga dramas. The museum provided a complete chronology of all of his roles, but you can also find these online, of course.

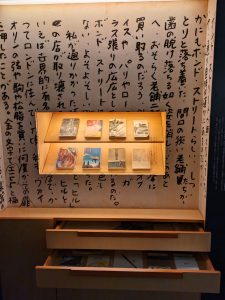

5: Essayist

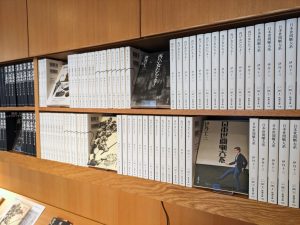

Itami wrote non-fictional accounts about many of his observations and experiences in life; in a different medium and time, the same was true for his films, with Ōsoshiki (The Funeral) taking inspiration from his experience with the funeral of Nobuko’s father, Marusa no Onna a reflection of entering a higher tax bracket following his success, and Daibyonin after a long hospital stay following his attack by the yakuza. His essay collections were showcased in the museum (one of which he designed to have its cover upside down, just for fun I guess), along with foreign nonfiction books he translated into Japanese – including playwright William Saroyan’s Papa You’re Crazy (1957), journalist Mike McGrady’s The Kitchen Sink Papers: My Life as a Househusband (1975), and a pretty mysteriously-experimental recipe book called The Potato Book by by Myrna Davis and Truman Capote which I checked out from my local public library last spring.

Reading this 1998 article in the SFGate about an interview with him just before his death gave me some interesting perspective on the above, and a deeper insight into his complex character. The article highlights some apt distinctions, per his description, in Japanese versus Western practices of film distribution, and it touches on his views toward Japan’s rapid postwar industrialization/urbanization, psychoanalysis (more on this later), and even things like enjo kōsai; I think his interest in what counted as transgressive – and to who, and why – showed up a lot throughout his work. His near-Freudian framing of Japan’s family dynamics and the role of gender in child-rearing puts his decision to translate a book about the author’s experience living as a stay-at-home husband for a year in certainly an enlightening context. Likewise, I’m sure he enjoyed exploring this further as a star in Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1983 The Family Game, a film that investigates social roles as the fragile (or arguably even completely fake) building blocks of traditional Japanese family structure, the pressure associated with these expectations, and how society reinforces them, even if we recognize the dysfunction. I know he wrote a lot about gender roles in everyday life, too, and I’d really love to read these works of his in the future. Across my favorites of his films and even in those I’ve enjoyed less, his work as a social critic and satirist has all been extremely thought-provoking, to say the least – in terms of influence on me personally, probably only Kurt Vonnegut comes close.

It’s such a shame that his essays have never been translated into English, remaining largely inaccessible abroad and even more unknown than his films. Maybe someday…

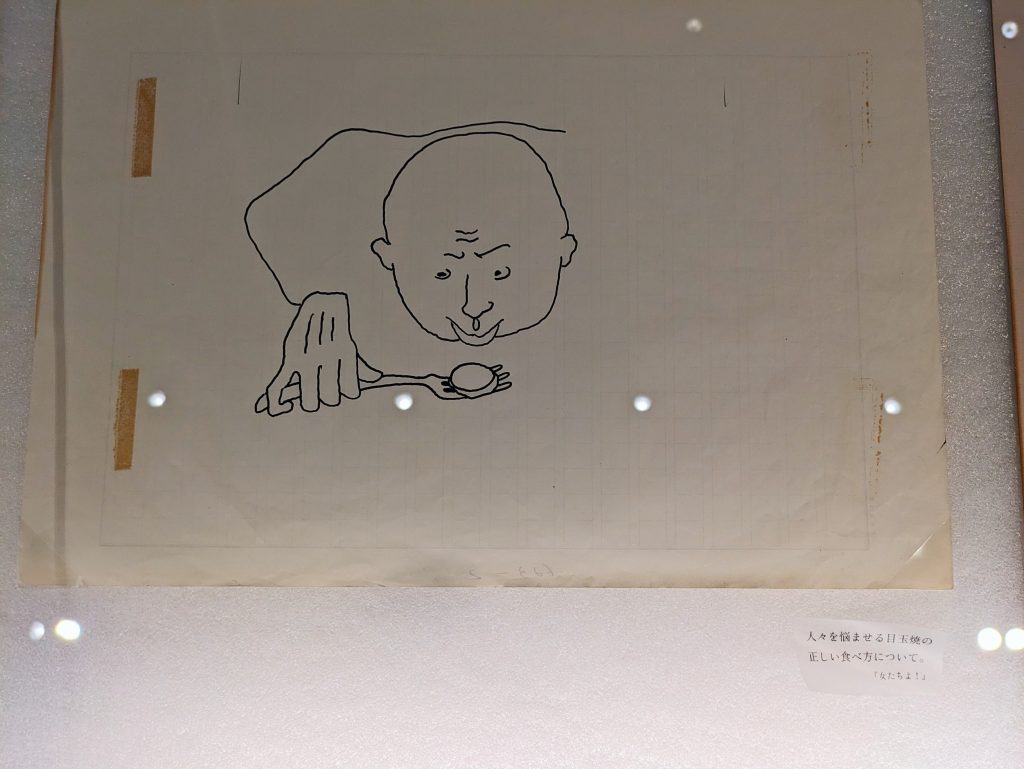

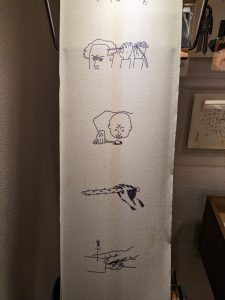

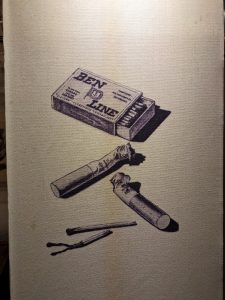

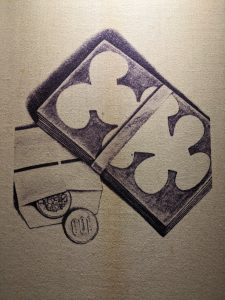

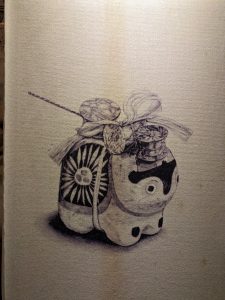

6: Illustrator

Itami drew his whole life, and many of his illustrations were showcased in this section on two large pulleys, the illustrations printed on a cloth that could be moved by rotating a wooden gramophone handle – in homage to his prized gramophone. Itami illustrated his essays too, starting with deformed line drawings and moving onto detailed, dense sketches – these various drawings of his were also present on the wall and in drawers showcasing some individual, original pieces of paper. He didn’t draw on drawing paper or in sketchbooks, but instead on the back side of manuscript paper in dark pencil. He did all sorts of drawings, from people to still-life objects to abstract diagrams, but his favorite thing to draw was cats. Cats were so important to Itami that they were, in fact, mostly not showcased here – they have a whole section to themselves later. He also illustrated and lettered all of the covers for his books shown in the previous section.

One part of this section that really interested me was the following quote of his, interspersed between the drawings on one of the cloths. It’s taken from what I can best loosely translate as “Chronicles of Everyday Japanese Stories” (日本世間噺大系 / Nihon seken-banashi taikei), a 1976 essay collection that he wrote while he was working at TV Man Union, Japan’s first independent TV production company. The book’s blurb on the publisher’s website starts by describing some of its contents: “A round-table discussion of menstruation that’s a must-read for husbands, a how-to for omelets that’ll make you want to head to your kitchen after reading it, a slightly-dreadful story of a Seitai chiropractor that’ll have you sitting bolt upright, and a symposium on Yase Dōji that makes the Emperor look like the old man next door…”3夫必読の生理座談会、読んだらキッチンに立ちたくなるプレーン・オムレツの作り方、ちょっと恐ろしくて背筋も伸びる整体師の話、天皇が隣のオジサンに見えてくる八瀬童子の座談会……

All translations by eli fessler. (As I was translating this, I went down hour-long Wikipedia rabbit holes learning more and more obscure things that even my Japanese friends and colleagues hadn’t ever heard of… man, I want to read his essays so bad.) Anyway, here’s the quote:

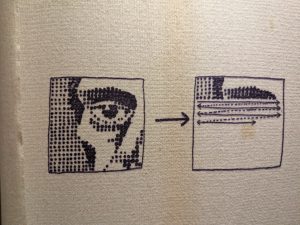

“What we call a ‘photograph’ is something that can only focus on one place. For example, if you focus on the front of a croquette, its opposite side won’t be in focus. Look at my drawing. You’ll come to see that the whole croquette – the croquette’s surface, each and every single one of the breadcrumbs – is in focus. It’s something that no photograph could ever hope to match.”4写真というものは一ヶ所にしかピントが合わぬものだ。たとえばコロッケの前手にピントを合わせればコロッケの向こう側にはピントは合わぬ。僕の絵を見たまえ。コロッケ全体⸺コロッケの表面の、あらゆるパン粉の一と粒一と粒、全部にピントが合っているのが判る筈だ。とても写真なんぞの敵うところではないのだ。

All translations by eli fessler.

In a way it seems at at odds with his filmmaking – while, sure, it was written eight years before he worked on his first feature, he had already worked as an actor for years at that point, and even made a short film (co-written with his first wife, who he was married to at that time) as a student 14 years prior. Maybe this is really about still life photography, and the moving picture was able to take on a different role in his eyes, eventually – or it was more a form of storytelling rather than precise visual art? But Itami did value preciseness, so who knows! Either way, I found this all quite interesting.

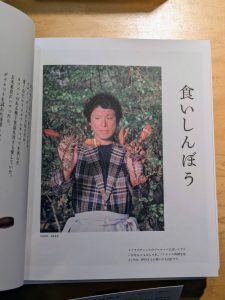

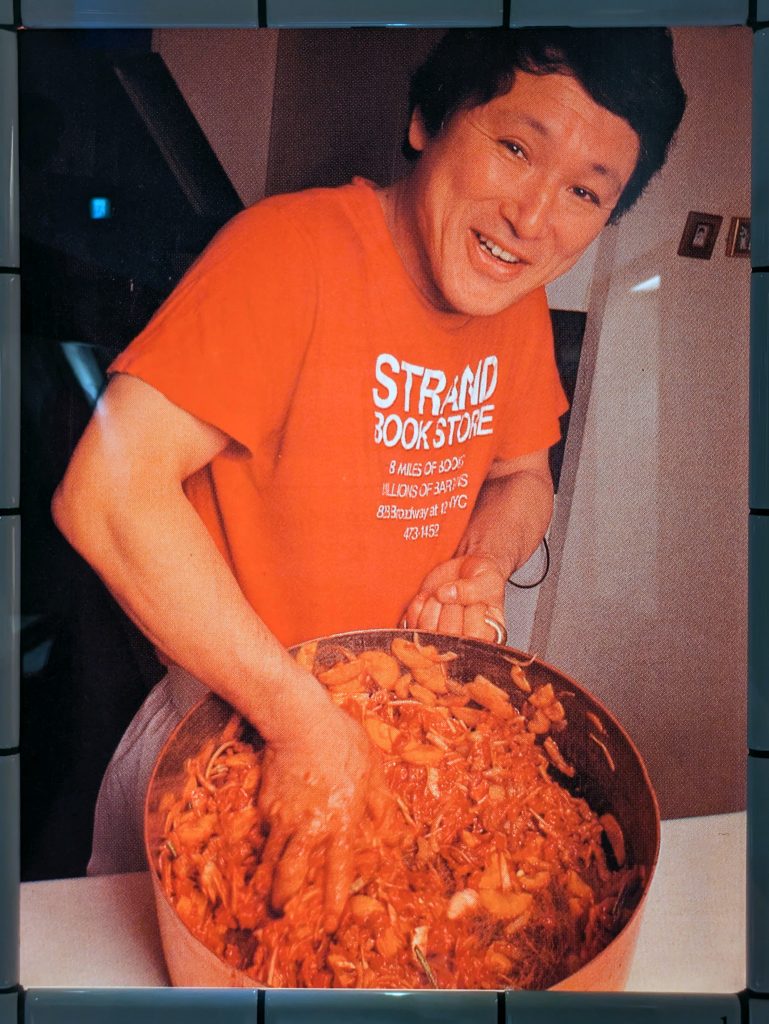

7: Culinary connoisseur

Here’s where we start to get into the Itami most people know, or probably which fewest readers here would be surprised about. Itami wrote about food in his essays a considerable amount, a fascination of his that quite obviously boiled over in Tampopo. The museum stated that he was most likely the first person to introduce the term “al dente” to a Japanese audience, and the theme of “how to enjoy spaghetti” comes up numerous times in his writing. He loved cooking as well, with his culinary skill described as that approaching a professional chef.

His first serious foray into food writing cooking came in the form of an article in the monthly magazine Bungei Shunjū (founded by the head of Daiei Film, Itami’s former employer) titled “French Cuisine with Me”, in which he described his home visits with anthropologists, psychoanalysts, essayists, and more, borrowing their kitchens to cook French food, and then eating the prepared meal together with them while discussing any topic of interest. Taking into account his love for both hand-lettering and food writing, I feel like he could’ve been friends with Mollie Katzen…

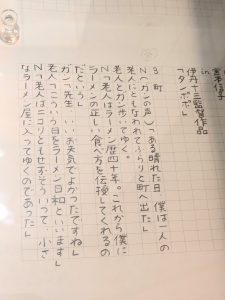

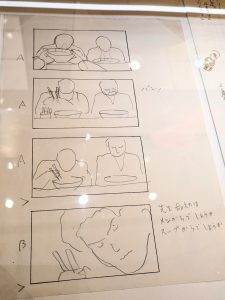

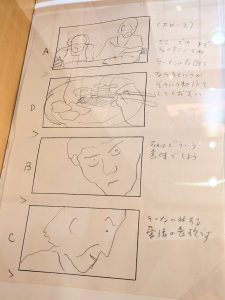

The part I loved the most, though – of this section, and maybe the whole museum – was seeing the handwritten script and a few storyboards from Tampopo. The storyboards show one of the first scenes in the film, taking place in the world of the book Gun is reading, as the young man converses with the master about the proper way to eat ramen:

Compare to the scene from the film: (subtitles by me, aiming for a very literal translation)

The character’s faces in the storyboards are so good, with such amusing expressions, and are so close to how they appear in the film. There’s no way this could’ve been drawn before casting, right?! I feel like this just made me appreciate the acting in the scene even more.

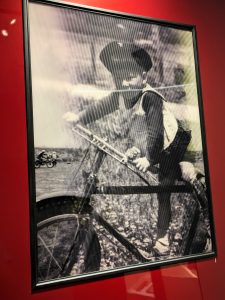

8: Vehicle enthusiast

This section will be short since I like trains and trams and buses and public transit, not cars (lol). Itami did, though, and he apparently wrote about cars a fair amount in Diary of Boredom in Europe. At age 48 he developed a love for motorcycles and obtained his motorcycle license, regularly riding to different movie theaters around Tokyo and even attending a training camp for motorcycle trials. Outside the museum was his last and most beloved car, a classic Bentley Continental, in a garage labeled with the number “8” to mark it as part of this section. The wall of the garage listed all six cars he had owned throughout his life. As part of the inside section, there were also two lenticular displays which contrasted him on a bicycle as a kid and motorcycle as an adult, and in a real car vs. an illustrated version of it.

9: Television industry worker

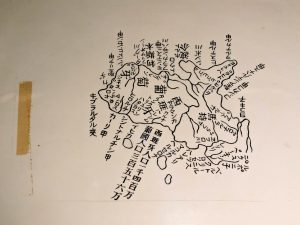

This section talked about Itami’s work at TV Man Union, where he was a host on the long-running (still going today!) travel program titled “I Want to Go Far Away”. Episodes of this show involved jaunts such as Itami traveling around the country to find the best oyakodon recipe and presenting it to the son of its creator, venturing to Nara to learn calligraphy, or interviewing the dwindling population of the rural Kozagawa, Wakayama. A 2005 reader titled The Juzo Itami Book, published by Shinchosha’s “The Thinker” magazine editorial board, gave details on other programs he worked on and wrote, e.g. “Juzo Itami’s Journey to Ancient Times” which involved Itami engaged in ethnographic linguistic interviews in both Japanese and German about dialects and pronunciation (!), and “Art Report” (one episode viewable here) where he introduced viewers to contemporary artists like Nam June Paik (!!!) and Andy Warhol.

The wall text speaks to how Itami believed that television offered more freedom and flexibility than the Japanese film industry, which at the time felt stagnant to him. I stumbled across this blog post by a Japanese writer who also visited the museum, watched some of the television program as a result, and described it as embodying an “experimental, free, anarchic way of expression”, characteristic of the 70s. Itami gradually moved from being a presenter to production staff and continued to hone his practice of meeting everyday people and listening to their stories.

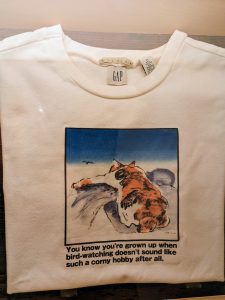

10: Cat lover

This section was simply presented in Itami’s own words:

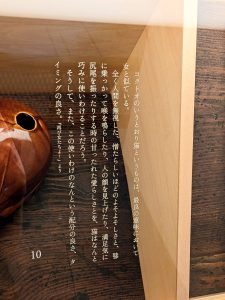

“It’s difficult when someone asks ‘Why do you love cats?’ The fact that I love cats is not a result of having some reason for loving them. Before one even thinks about things like ‘reasons’, the fact that you already love something already exists in full force. That is to say, I love them because I love them, or rather, it likely can’t be helped.”5「『どうして猫が好きなの?』と、いわれても、それは困る。私が猫を好きなのは、なにか理由があってその結果好きだというのではない。理由などあれこれ考えるより以前に、すでに好きだという事実が厳存しているのであって、いわば好きだから好きだ、とでもいうよりしょうがなかろう」

All translations by eli fessler.“The dignified aura of cats, but also that irredeemable ignorance – I love both of those parts.”6「私は、猫のあの凛としたところと、あの救い難い無知みたいなところ、両方好きなのですね」

All translations by eli fessler.“To start, I’ve been living with cats ever since I was born. No matter which period of my life I reflect on, there’s barely been a time I haven’t been surrounded by cats. For each period, it’s ‘ahh, that was the time with this cat’, ‘ahh, that was the time with that cat’. I immediately match it with any one of a variety of cats. The truth is, for me, I cannot imagine a life without cats.”7「そもそも私は生まれた時から猫と共に暮らしてきた。私の過ぎ去った人生を振り返ってみても、周囲に猫のいない時期というのが殆どない。各各の時期が、ああ、あれはあの猫の時分、ああ、あれはこの猫の時分という工合に、様様な猫たちのだれかれと直ちに一致する。実に、私において、猫のいない人生は考えることもできぬのである」

All translations by eli fessler.

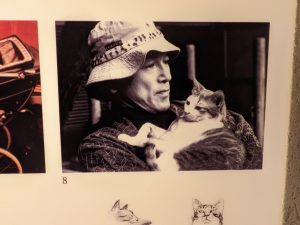

The setup for section 10. Itami’s dad liked cats, too, shown in photo 1. Itami’s cat, Koganemaru, is shown with him in photos 2–4. The cat in photos 5–6 was named Nyankichi, picked up by his oldest son one day on the way home from school. Itami liked to train cats to massage his back, too, a rather profitable exercise…

A cat-shaped ceramic pillow from Itami’s home.

Itami drew many cats over the years in various styles, using pencils and brushes, in grayscale and color.

11: Psychoanalytical enlightener

This section of the museum described how Itami’s view on life began to shift shortly after having two kids with Miyamoto and moving to Yugawara, Kanagawa Prefecture to better raise them, surrounded by nature. (The aforementioned The Juzo Itami Book describes this as due to Itami taking on new, less-traditionally-masculine roles of childcare and housework, which gave him invaluable experiences.) An avid reader, it was around this time that he discovered Japanese psychologist Shu Kishida’s 1977 essay collection Lazy Psychoanalysis (ものぐさ精神分析 / Monogusa seishin bunseki). Itami became a believer in his theory of “Illusionism” (唯幻論 / Yuigen-ron); the men befriended each other and the following year co-published a work titled The Adult in the Baby Incubator: Lectures in Psychoanalysis (哺育器の中の大人 [精神分析講義] / Hoikuki no naka no otona [seishin bunseki kougi]), which took the form of transcribed conversations between the two.

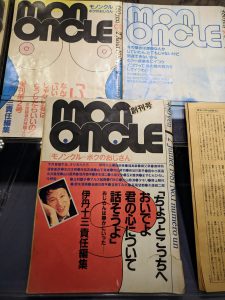

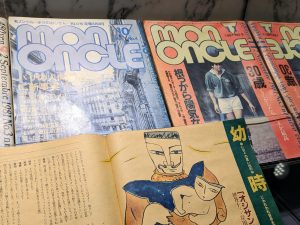

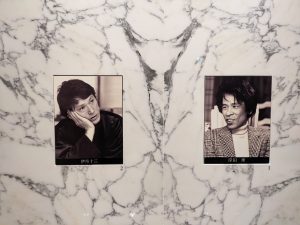

Their partnership soon led to Itami (at age 48) becoming the editor-in-chief for a new magazine titled Mon Oncle (モノンクル / Mononkuru), French for “My Uncle”. The publication was aimed at general readers and tried to casually present issues of the time through lenses that were likely different from those of one’s parents, introducing a variety of new viewpoints and analytical angles. The magazine only ran for six months, until November 1981, with Itami saying he found it interesting but ultimately was not suited for the job. (For those curious, this interview says it’s not confirmed as to whether it drew inspiration from the Tati film of the same name or not…)

This designation seems to be fitting for Itami, too. In writing this post, I was searching for others who had visited the museum and written about their experience as well, and came across this Japanese blogger who writes, “One of the ‘uncles’ I most deeply respect is Juzo Itami.” She gives a footnote to define her quotative use of ‘uncle’: “An older gentleman who is so playful and kind that everyone feels related to him.” I concur: this is the exact spirit and feeling Itami exudes.

12: Commercial writer

I loved this section because this is where weird Itami really started showing off. I mean, he was unabashedly unconventional in all his other pursuits, too, but this is where we first start to see his literary prowess in video form – and not only that, but he was the one delivering the lines, too… because who better? His commercials (or “CMs” in Japanese) were frequently him giving monologues; he was well-known and well-loved enough at this point that his very presentation of a product, however he presented it, was proven to be amusing, captivating, and thus likely leading to success. It was a perfect combination of Itami the writer and Itami the actor. The museum highlights this CM for Seiyu, a department stores and supermarket chain:

“Y’know, when it comes to women, I think they’re geniuses at socializing. After all, since they have babies inside of their stomachs for ten months, it means that they’ve really got down the essence of interpersonal relationships. So when it comes time for a mid-summer gift, wives are by far the best [at choosing gifts for people]. Like sōmen for Sato-san, or tatami iwashi for Mori-san. She knows just what to get to make them happy – just like THAT. And they’re cheap!”8「僕の考えじゃ、女の人っていうのは、付き合いの天才だと思うわけです。そりゃなんたって、お腹の中に赤ん坊を十ヵ月も入れているわけですから、人間関係の根本っていうものを押さえているわけです。だもんだから、お中元なんてことになると、これはもう圧倒的に女房の方がうまいわけ。佐藤さんに素麺とか、森さんに畳イワシとかね。相手の喜ぶものってのが、パッとわかっちゃうわけです。しかも安いものでさ」

All translations by eli fessler.

There’s quite a few Japanese cultural references here that are hard to “localize” away – I’m trying my best to use hyperlinks liberally in this post – but even without understanding all the nuance, the humor assuredly remains. Here’s one more. I’m unsure if this CM was actually produced as-is-written, but the museum included it on the wall of this section, yet again showing his unorthodox approach toward… well, everything. This is the narration from a draft of a (very meta!) commercial he wrote for Ajinomoto:

“This is a serious commercial, but its flaw is that it says everything it wants to say, so it’s hard to understand as a result. As for the product itself – I think it’s good.”9マジメなCMですがいいたいことを全部いってるためにかえってわかりにくくなってるのが欠点ですね。商品そのものはいいと思いますよ。

All translations by eli fessler.

The image on top is from one of Itami’s commercials for Ichiroku Tart, a local specialty of Matsuyama and Ehime Prefecture. More on this later!

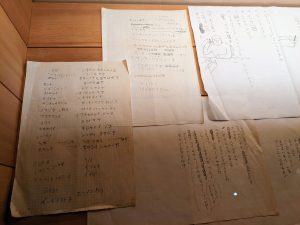

Handwritten manuscripts for various commercials, including Seiyu, Ichiroku Honpo, Ajinomoto, National (now Panasonic), etc.

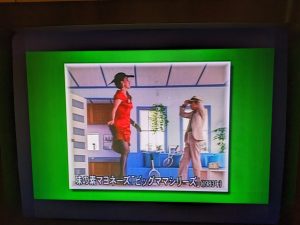

And here’s a video of Itami wriggling around on the ground to promote mayonnaise. Because why not.

13: Film director

Here’s the Itami most people know. There wasn’t anything in this section that was super new to me, but all of his film posters were on display, along with some behind-the-scenes photos of him directing, some manuscripts for Daibyonin, and a few of the iconic costumes and props from various films.

A quote from his “production diary” of The Funeral is also present, perfectly summarizing what led him – despite his myriad talents and forays into various fields of work across half a century – to arrive at and instantly feel fulfilled in directing films:

“Up until now, I’ve tried my hand at various forms of expression, but I have a feeling that directing is the best apparatus to bring out my whole self, in its entirety. It is really efficient at burning up my whole self (lol). In other words, for me, there’s no other form that expresses my entire self.”10僕は今まで、いろいろな表現形式を試みてきましたけど、自分全体を丸ごとすくいとる仕掛けとしては監督が一番という気がしましたね。自分全体を燃やせて実に効率がいい(笑)つまり、自分丸ごとの表現形式として、僕としてはこれしかない⸺

All translations by eli fessler.

One thing I thought was interesting is that the negatives used as decoration, lit up behind the film posters and on-set photos, include English subtitles?? They’re all from A Taxing Woman; here’s a more detailed photo where you can see the subtitles if you zoom in. The film was indeed released in the US (with a very cheesy/punny tagline: “He has a yen for her, but he won’t tell her where it’s hidden”) and perhaps the museum was able to obtain negatives for this version, and they’re less valuable than the original copies, thus suitable to be shown off? I only noticed this when looking back at my photos so couldn’t ask the staff! I guess I could always call…

As seen above, The Funeral originally had a different title: Autumn for Wabisuke’s Family (侘助たちの秋 / Wabisuke-tachi no aki). This name was scrapped after shooting got scheduled for summertime. The museum informational pamphlet shared a few other ideas, too: Parting Day (別れの日 / Wakare no hi), Greetings in the Wind (風の中の挨拶 / Kaze no naka no aisatsu), and Kind People (やさしい人々 / Yasashii hitobito).

Finally, large size posters were viewable in a moveable book-like display for all ten of his films, which also showed the back sides of the original chirashi flyers. You can see most of those scanned on eiga-chirashi.jp, but here are links to the ones they’re missing: A Taxing Woman front & back; A-Ge-Man front & back; Minbo front & back.

Special exhibition: “Eating, drinking, cooking.”

This was the title of the rotating exhibit in the Itami Juzo Museum, located in the second and third rooms on this side of the building. It was around the same size as the first room, and it’s been on display since July 2023. Unfortunately, pictures weren’t allowed in this exhibition, and I wasn’t as interested or invested in Itami’s favorite cookware and such, compared to everything described up until now… in addition, the page about it on the museum’s website (in Japanese, use Google Translate lol) actually gives a great overview with a few photos too. As a result, this part of the blogpost is going to be pretty sparse, at least compared to the above.

In cases where something seemed interesting but I couldn’t understand the language used, for the purpose of being able to read & more-carefully translate the text later, the staff were OK with me taking a couple photos. Since it seems quite a few others (e.g. Japanese bloggers, Twitter users) have done this as well I’m hoping it’s not a horribly egregious sin to share a few limited parts this exhibit here which are all already public – only the truly best parts. For example:

As a wonderfully-succinct caption to the drawing, this is the funniest piece of text in the entire museum: “The correct way to eat a fried egg, which is something that troubles people.”

The real-life lemon squeezer featured in drawings and on the cover of Diary of Boredom in Europe. One of Itami’s favorite objets d’art.

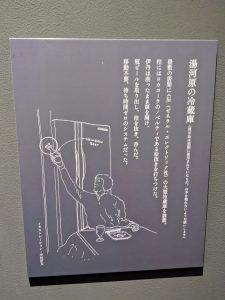

This plaque tells the story of how Itami installed his refrigerator and a bottle opener in his living room so he could drink beer with no hassle. “It was a system with no unnecessary movement and zero waiting time.”

Along with food-related drawings and illustrations from his essays, the museum showcased a lot of artifacts taken from Itami’s home in Yugawara (which is, by the way, where The Funeral was filmed – yeah, he literally just shot it all at his house. incredible). Both small-scale objects like bowls, utensils, sake cups, etc. and larger-scale like his oven and fridge were showcased. The following smaller room was dedicated to slideshows and videos, such as an episode of “I Want to Go Far Away”. The most exciting thing I learned here is that a cookbook is due to come out in the future which will feature recipes from Itami’s books – namely, recipes that have naturally continued to evolve, that other fans of Juzo Itami have taken and adapted into their own styles. It’ll be called “Itami Recipes My Way” (私流伊丹レシピ / Watashi-ryuu Itami reshipi). I’m seriously excited and hope it actually releases at some point, preferably soon!

Finally, there was a small section dedicated to Juzo Itami’s father, Mansaku. In his 40s, Juzo expressed the desire to build a museum dedicated to Mansaku in Matsuyama, and suspected that his father had died feeling that he (Juzo, his son), had been his biggest regret in life (ouch…) While he wasn’t able to accomplish this himself before his death, Miyamoto did it for him, building a museum both dedicated to him and, in part, his father. What a wonderful tribute.

Handmade karuta cards crafted by Mansaku Itami.

Café Tampopo

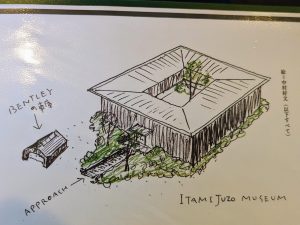

Fooooooooood!!! What would an Itami museum be without food? OK, well, not quite yet, but the the bold heading kinda spoils that there’s going to be food, right? If you don’t have a sense of the building layout yet, it’s a square with a hole in the middle. Pretty much exactly this Unicode character: 🞒

One of the pamphlets they gave me actually shows this well (this clip taken from a very special DVD that I’ll be talking about later):

In the middle of the building is a courtyard with a tree in its center, and an outdoor wooden walkway running around the perimeter. All this to say: it was nice!

The museum was constructed by architect Yoshifumi Nakamura and it feels like a pretty unique space, with Miyamoto’s intentions being to make it so visitors could feel as if they were visiting Itami’s home. Nakamura helped design all the contents and text of the museum galleries, and is also on the selection committee for the Juzo Itami Award (NB: yes, I created that Wikipedia article myself during the course of writing this). He’s a huge Itami fan, having discovered his essays in his 20s, even coined a word to describe himself: “Itamist” (イタミスト). I’m one too! You can read an interview about his work with the museum (in Japanese) here.

OK, now actually onto the food. The cafe is called Café Tampopo and plays the soundtrack from the film for you to enjoy while you dine. It doesn’t have enough for anything you eat there to be called a meal, but definitely has some very nice snacks and treats (and I do love snacks and treats). There were also some books to read in the cafe, like an overview of the museum itself and more about Nakamura, a guide to the gift shop, and readable copies of the books that the museum sells, like a collection of storyboards for the entirety of The Funeral.

Inside the cafe. This shows about 90% of it; the counter where you order was just off the right side of the photo.

I ordered the Juzo manju, both the cheesecake and chocolate cake, and the Ehime mikan nomi-kurabe set. Ehime Prefecture is famous for their mikan oranges, and they are everywhere in the city of Matsuyama. There is mikan soft serve. There is orange juice served from faucets of public juice trucks. There are shops dotting every other street selling orange-colored tangerine plushies and packs of orange jelly and you name it. The symbols for Wi-Fi look like oranges giving off radio waves. And most importantly there is Mican (みきゃん / Mikyan), the yuru-chara mascot of Ehime who is a cross between a mikan orange and a puppy. You can see how stupidly cute Mican is on the Ehime prefectural website here. And then there are people wearing masks with pictures of Mican printed on them, and so on and so on. I seriously don’t know how to convey how much orange stuff in this city, but this blogpost starts to give you a sense of it. Anyway, the “nomi-kurabe set” or “drinking-comparison set” let me try out three different varieties of mikan juice from three different places (and they did indeed actually taste very different!) As a fruit-lover it was pretty great.

“But hey, wait, what about the chocolate cake you mentioned” you ask?

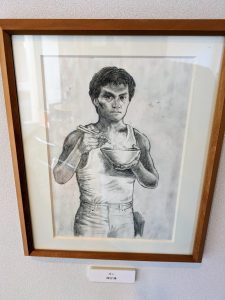

You just know Itami would have loved this to death. On the wall were also the original drawings Itami did for the original Japanese poster (scroll down to the second image, the yellow one) of Tampopo:

The Man in the White Suit (Kōji Yakusho)

The wall text next to the mini-gallery said that Itami had suddenly began drawing portraits of the cast one day on set “like he was possessed”, and then graphic designer Samura Kenichi put them together into a poster. Apparently Ken Watanabe’s likeness was the hardest to capture, and after drawing their faces and bodies, Itami went back with a mechanical pencil and added details like the steam from the ramen noodles and the wrinkles in their clothes.

Unfortunately the neighboring storage room along the north wall, which houses thousands of other Itami memorabilia, is only open for a guided tour two weeks out of the year, exclusively for members of the museum (¥3000 yearly fee). Next time!

Gift shop!

This is the part of the blogpost where I describe to you why I have no money anymore. OK, mostly joking, but least the yen is weak so if I’m thinking in USD it doesn’t feel like I spent that much…

The gift shop is back in the museum’s entrance area, next to the door, tucked into the opposing corner from the reception. They had quite a good variety of stuff which I’ll mostly show off in photos below instead of describing it in prose. I will say, though, that they do also have an online shop, so if you’re really desperate for any of this stuff (i.e. enough to pay to use a proxy/forwarding service if you live outside of Japan) you can in fact get it, or at least most of it. And you don’t have to pay in cash like was required in-person at the museum! (Classic Japan.)

The gift shop. Postcards, T-shirts, and tenugui towels on the right, books against the back wall, lots of trinkets in the middle.

Book of The Funeral storyboards. You can choose between two cover designs! There was also a museum guidebook with two different covers.

Regarding the “holy grail” above, it’s the DVD for a documentary titled Juzo Itami: The Man with 13 Faces (13の顔を持つ男-伊丹十三の肖像 / 13 no kao wo motsu otoko: Itami Jūzō no shouzou), my newly-acquired copy seen in the bottom left of the photo directly above. The film is, as of this writing – confirmed by years of searching and talking with few other hardcore fans who have done the same, who I actually met and became friends with in the first place via our searching – not anywhere online, and not available outside of buying the physical disc here in Japan. It’s a 2.5-hour long documentary by Toshirō Uratani, a producer and director who worked with Itami on “I Want to Go Far Away” at TV Man Union. He’s known for his legendary behind-the-scenes documentary films. His other works include The Making of “Tampopo” (which was finally released in the West by Criterion in 2017, complete with English subtitles alongside their 4K restoration of the film) and a three-part, 400-minute documentary filmed over the course of two years called How Princess Mononoke Was Born about the creation of the (best) Ghibli film. I can’t watch to finally watch it.

After the museum, I actually went to one more very-related place: the Ichiroku Tart store. Ichiroku is the company for which Itami produced those dessert commercials so many years ago that I briefly mentioned above. Its history is that it was founded in 1951 in Matsuyama by a man named Ichiro Tamaki. (Appending one syllable onto the end of his first name made it “ichi-roku”, or 一六, ‘one-six’. An interesting numerical connection with the man whose name was ‘one-ten’ and then ‘thirteen’, no?) His son Yasushi Tamaki later took over the business, and when it was time to cast an actor for their commercials, he chose Itami because of his deep ties to Matsuyama. The two forged a friendship and business partnership; when Itami himself became a film director with The Funeral, Ichiroku invested in its production. Tamaki was appointed the head of Itami Productions, and has continued to support Itami, his works, and his legacy to the current day.

So, funnily, this confectionery business and Itami’s legacy have become deeply interwoven; the ITM Itami Memorial Foundation (which runs the museum) is part of the ITM Group, which also runs Ichiroku, and Tamaki is the chairman of both. The museum is also built right next to the ITM head office building (literally in their now-former parking lot!) and across from one of the dessert shops. And while “ITM” officially – apparently – stands for “Ichiroku Total Mixture”, I can’t help but feel that this 1991 “group identity” rebrand to those familiar three syllables miiiight have been influenced, even if only a little bit, by I‐Ta‐Mi.

The Ichiroku Tart store next to the museum was closed, so I went to this one by the place I was staying.

Kadomatsu and a shimekazari for New Year’s outside the building. They had many other desserts inside, too.

Lots of flavors of Ichiroku Tarts! Not pictured, but some orange ones even had Mican on the packaging…

Itami’s legacy is incalculable. I stopped by Takayama, Shikoku’s second biggest city, for a couple days on my way home and stayed at an Airbnb run by an older couple who rented out a couple of spare rooms in their house. I met them the day after I arrived while some of their friends were over helping them move furniture, we chatted, and they asked why I came to visit – so I told them that my favorite director was Juzo Itami and I was there to visit the memorial museum. They acted a little surprised but asked my favorite movie of his, seemingly testing the waters a bit. As soon as I said “Tampopo” and “Marusa no Onna”, the two women shouted “MARUSA!!!!”, incredulous, and began quoting some lines from the film, laughing to each other. They were shocked – why do you know Juzo Itami??? We love Juzo Itami too! Instant connection.

It was like I helped resurrect this core memory of some wonderful time from their youth, watching this hilarious, clever film with a strong female lead, totally clashing with the trends of the industry at the time, bravely critquing the very culture it definitionally existed within, standing out as uniquely distinct from even anything that’s come out since… it just made me so happy. He was one of Japan’s most important filmmakers of the 20th century. They said: “It’s like you’re more Japanese than Japanese people… it’s a little scary… why do you know this…” – because I think a random foreigner mentioning Marusa no Onna to them 26 years after Itami’s death in the city of Takamatsu, Japan was definitely not something they ever expected to happen.

But of course they know Juzo Itami – because everyone here knows Juzo Itami. He was, arguably, Japan’s most important filmmaker of the 20th century. Or at least one of them. And, around the world, everyone knows Akira Kurosawa. Everyone knows Hayao Miyazaki. Why not Itami?

I hope you had fun reading this insanely long post (sorry! or not!) and that it inspired you to watch some more of Itami’s films… or re-watch them, which might be more likely if you made it this far. Or even go visit the museum yourself.11If that’s not possible, and you want to get more of a sense of the space itself, there is a documentary exclusively about the museum and its creation called Itami Juzo Kinenkan no “13” floating around online, originally bundled in a Blu-Ray box set of his films from 2012… It’s so worth the trip. I’m so lucky to have been able to go. And I’m so lucky to be able to experience his films, and to be able to call him my favorite director. But even without a physical reminder of his life and presence, even without a wonderful museum, filled with love, with walls that will likely be standing long into the future, Juzo Itami will never die.

This is just fantastic, thank you so much for finding, translating and sharing so much information, I’m glad you had such a lovely time at the museum. I hope to go someday soon!

Saoirse, thank you for reading, so happy you enjoyed!! I hope you’re able to go someday as well!

Outstanding, passionate, knowledgeable commentary! My eyes and my heart have been opened! And now I want some ramen and a bird lemon squeezer :-)

I also love little trinkets like that, ha. Thank you!!

Thank you.I read every line of it, and photos.I’m a huge fan of Juzo Itami with the Tampopo film, of course.Who can resist this vehicule ? humour and search for hapiness in the cooking

I’m a huge Itami fan as well (as you can surely tell, haha) – super happy that you connected with the post so deeply and enjoyed reading it, much appreciated!! :)

This is an incredible report about a trip to a museum. Itami is my favorite director as well and I had not a clue, that a museum like this even existed. But since it is very unlikely that I will ever get there on my own, I truly enjoyed your writing about it and the photographs. Somehow, it almost feels like I have been there.

Ales, thank you for your kind comment! Sorry it took me a while to see it & reply. Always so happy to find others who are a fan of him and his work. That was essentially my goal in writing this post, so I couldn’t be more glad that that’s what you were able to get out of it, too. :)

I scrolled through your film-related blog as well, and while I don’t speak German, please do stay in touch! And I do hope you happen to be able to make it to the museum someday, somehow!

Very very cool to see more love for Juzo Itami!

Thank you for this great overview of a museum I would love to visit one day.

Alas, it’s so far out of Tokyo I might not ever reach it on my limited timed trips.

Do you happen to know if Nobuko Miyamoto still welcomes people to the museum?

An article of 2011 I found mentioned there was a schedule for her appearance but that is of course over 10 years ago.

Thank you for comment, Jeroen! Sorry for my very delayed reply, which came as I was traveling and away from my computer with enough energy/time/screen space to give you a proper reply! I think it’s quite doable if you’re visiting western Japan (e.g. Fukuoka, Hiroshima, or really anywhere around there) and would say the trip’s very worth it; I loved Matsuyama, and Shikoku as a whole, and am planning on going back in the spring of next year to explore and see more on the island. I hope you can make it! Always fun to find other fans of Itami too (I followed you on Letterboxd, stay in touch!) And do let me know if you’re in my area or if we might be crossing paths. :)

Unfortunately I don’t know if that’s a thing she does anymore. Surely she shows up for special events like the yearly guided tours for members (or, I’d assume anyways!) but I’d just be guessing outside of that. Maybe for some screenings or something, or randomly, but perhaps not on a fixed schedule or with advance notice… I bet you could email them and ask to see if they have any more info to share! Please do let me know if you find out!

I loved this read, thank you very much. I’m early in my Itami journey but can’t wait to learn more. I wish his writings were translated to English.

Enjoy!!! And thank you for taking the time to comment, Craig! You’re really in for a treat; his works are all so, so special. Getting to see many of them for the first time would be an incredible experience to be able to have again (although the rewatches are just as wonderful in their own ways!) Really, you’ll have a blast.

I am *desperate* for that too. It’s a little unbelievable that – at least as far as I’ve ever been able to find – not even his most well-loved or impactful quotes, or snippets, much less a single essay, has been translated by… anyone, ever, for so many decades. My Japanese is really not quite good enough to understand the type of smart, unique, non-fiction writing he was doing, or really “get” the context of the world he was writing in, or probably most importantly appreciate his voice in a natural way. I’d be lying if I said that in writing this post, the thought didn’t cross my mind that a publisher or literary translator (or historian, academic…) may someday come across it and become enamored & inspired enough by my attempted depth of exposition that they pitch it to someone who might be able to something about it……… :)

Just wanted to say I quoted a huge chunk of your paragraph about Ehime and mikan in a deck I made for work. I really liked the tone of it! I was tasked with researching locations in Japan for a film we’re developing—I immediately thought your blog might come in handy.

Oh wow, very cool, thank you so much, and thanks for the kind words & taking the time to leave a comment too!! :) You funnily enough left this comment just after I got back from being in Ehime for my second time during a Golden Week trip, amazing timing! I hope you can come visit some day – Shikoku is really really great. I followed you back on Letterboxd too!